One book unsettled me with its closeness to evil, the other impressed me with its cold, deliberate distance. Both lingered long after the last page.

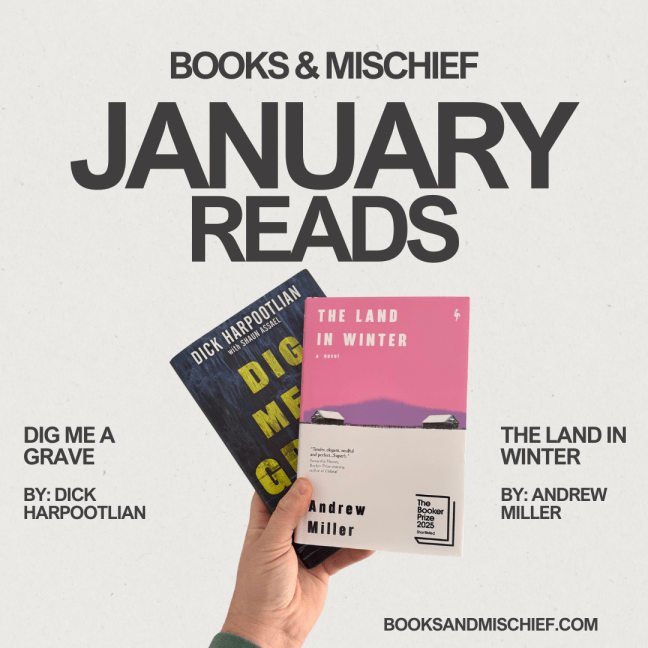

January arrived with long nights and quiet hours, a space that invited reading without interruption. This month held two books that could not have been more different in form, yet felt strangely aligned in temperament: Dig Me a Grave by Dick Harpootlian and The Land in Winter by Andrew Miller. Both are concerned with restraint. Both orbit violence, one explicit, the other buried. And both left me thinking about distance, how close a writer dares to stand to their subject, and what happens when that distance collapses.

I read Dig Me a Grave with the afterimage of The Final Truth still lingering, which felt unavoidable, like trying to look at South Carolina without also seeing its humidity. Harpootlian’s version of Pee Wee Gaskins is cleaner, more procedural, less mythologized, and in that way perhaps more honest. The violence is still present, but it is not performing for the reader. It simply exists. There is no narrative flourish asking for our fascination, no invitation to marvel at evil. That restraint makes the book more unsettling than spectacle ever could.

What ultimately held my attention was Harpootlian’s proximity to the story. His closeness to Gaskins, and more disturbingly, the moments when that closeness brushes against his own family, introduces a genuine sense of menace. Those passages collapse the safe distance between observer and subject. The horror is not just what Gaskins did, it is how near it comes, how easily it bleeds into ordinary life. The book is at its best there, when it refuses the comfort of separation.

Still, Dig Me a Grave lingers too long at the end. The conclusion loosens when the material demands precision. Restraint, which serves the narrative so well throughout, is briefly abandoned when it is needed most. It is not enough to undo what the book accomplishes, but it leaves a faint sense of imbalance, as though the author stepped back just when the silence should have been allowed to settle.

I finished The Land in Winter during South Carolina’s brief flirtation with actual cold. Another Booker read, another novel shaped by aftermath. Set in the quiet rubble left by war, Miller’s book moves slowly through frozen landscapes and interior lives, concerned less with plot than with endurance. It is a novel about what lingers beneath silence, grief unspoken, desire deferred, damage that refuses to announce itself.

The atmosphere is impeccable. The cold feels earned, not decorative. Every page seems weighted with restraint, with the sense that anything overt would be a betrayal of the lives being depicted. And yet, despite its beauty, despite its craft, it never quite reached me. I found several of the characters cold in a way that felt less intentional and more alienating. Insufferable, at times. Possibly that is the point. Possibly it is a book for another season, another version of myself with more patience for quiet suffering.

What struck me, reading these books back-to-back, is how differently restraint can function. In Dig Me a Grave, restraint sharpens the menace. It pulls the reader closer to something they would rather keep at arm’s length. In The Land in Winter, restraint creates distance. It preserves atmosphere but withholds intimacy. One unsettles by proximity, the other insulates by design.

January, it turns out, was less about what I read than how I responded. One book unsettled me by refusing spectacle. The other impressed me without fully opening itself. Both asked for patience. Only one rewarded it in a way that lingered. And perhaps that is what winter reading really reveals, not just what a book is, but where we are when we meet it.